In The Footsteps of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Hester, Harems and Hamams…

When Lady Hester Stanhope arrived in Constantinople in November 1810, she was well aware that she was following in the footsteps of the celebrated Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, whose glamour can be glimpsed in this rather well-known portrait (pictured here). She arrived in 1716 to follow her husband, who had been appointed Ambassador to Turkey. ‘Lady W. Montagu’s’ musings on life in Turkey and in particular her insights into the most intimate details of the lives of Turkish women, had been published after her death in 1761, and made her the posthumous literary celebrity of Hester’s parents’ generation.

When Lady Hester Stanhope arrived in Constantinople in November 1810, she was well aware that she was following in the footsteps of the celebrated Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, whose glamour can be glimpsed in this rather well-known portrait (pictured here). She arrived in 1716 to follow her husband, who had been appointed Ambassador to Turkey. ‘Lady W. Montagu’s’ musings on life in Turkey and in particular her insights into the most intimate details of the lives of Turkish women, had been published after her death in 1761, and made her the posthumous literary celebrity of Hester’s parents’ generation.

Hester was clearly keen for her own accounts of life in Constantinople to be similarly preserved and praised. Around this time she began the habit of carefully copying her own letters, and sending her friends versions of ones she thought especially good. She relished the outrageous. To one correspondent, she boasted that “one of the greatest men here likewise is to show me his Harem himself when he comes back from Bagdad [sic] where he has been cutting off heads.” This was her newly acquired friend, Hafiz Aly, the Kapitan Pasha, the head of the Turkish navy. When the weather improved, on one of her visits, Hester saw one of these severed heads for herself; “the poor head was handed about on a silver dish as if it had been a Pine Apple,” the brain, eyes and other soft tissue extracted and replaced with perfumed cotton.

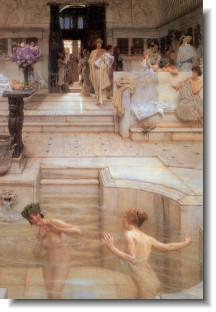

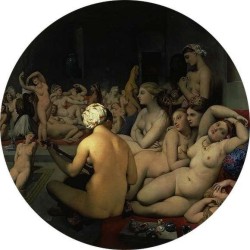

But Hester’s male correspondents were more interested in the goings-on behind the walls of the women’s quarters of the Turkish baths, the hidden world of the hamam. No doubt the idea of being able to thaw out in a steamy, marbled room, with copious supplies of warm water would have been irresistible to Hester, who, when she first arrived in Constantinople, had to put up with rather grim lodgings, the only heating being a paltry tandour oven which made the room reek terribly of smoke. Having read Lady Montagu’s description of the hamam, Hester would have wanted to see the real thing, a secret experience unavailable to men. Ingres drew on Lady Montagu’s accounts to inspire his many highly erotic, dream-like paintings of bathing odalisques in Le Bain Turc. But outside such imaginative reveries, the punishment for any man who attempted to intrude upon these private scenes (other than the Sultan himself, or his eunuchs) was death.

Constantinople contained the most beautiful and elaborate hamams in existence: never mind that the most elaborate were available only to women in the imperial harem. Hester soon declared herself an addict. Early in her stay, she had to make do with the public Cagaloglu Hamam,a gift to the city from Sultan Mahmud I, not far from the Hagia Sophia. The far-more impressive imperial hamam used by the Sultan’s wives and concubines, closer to the Topkapi (which today is used as a national carpet shop), she had only been able to admire from the outside. The Cagaloglu baths are still impressive almost two hundred years later. The interiors in the women’s quarters have changed little; still the same central octagonal slab beneath a domed ceiling; light streaming in through star-shaped niches, bare-breasted women only partially visible through the vapour. Wrote Hester:

Constantinople contained the most beautiful and elaborate hamams in existence: never mind that the most elaborate were available only to women in the imperial harem. Hester soon declared herself an addict. Early in her stay, she had to make do with the public Cagaloglu Hamam,a gift to the city from Sultan Mahmud I, not far from the Hagia Sophia. The far-more impressive imperial hamam used by the Sultan’s wives and concubines, closer to the Topkapi (which today is used as a national carpet shop), she had only been able to admire from the outside. The Cagaloglu baths are still impressive almost two hundred years later. The interiors in the women’s quarters have changed little; still the same central octagonal slab beneath a domed ceiling; light streaming in through star-shaped niches, bare-breasted women only partially visible through the vapour. Wrote Hester:

“I go into a vast chamber filled with steam and lay down on the marble floor, they through basins of water over me, soap me all over with a whisk like a horse’s tail, then immerse me in a large bath, roll me up in cloths and lay me on a bed where I fall asleep and wake hungry and refreshed…the women make a parade of bathing; their patterns are set with pearls, the cloths they are wrapped in are worked with gold and coloured silks. A bath full of Turkish women is a magnificent sight; they are like so many statues in graceful drapery and some without any…”

Hester first would have passed through a private pavilion where groups of Turkish women reclined in semi-attire on divans, drinking coffee or sherbet. She would have stripped in a latticed cubicle, leaving her clothes and belongings to be attended by a guard. Wearing only a cotton wrap, she would have loosened her hair to enter the bathing hall. Here, she would have been led through a steam-filled enclosure, and gazed about her through archways to see numbers of women, many of rank, and their slaves, who were as naked from the waist up as their mistresses, combing their hair, massaging their limbs with rough sudsy whisks and pouring water over their bodies from copper basins. All teetered skillfully across the hot marble floors on wooden stilt-like clogs, some even carrying infants and small children, whose cries added to the cacophony. She thought their “eyes, their brows & noses are charming” and that they had “finely proportioned figures…fine busts, & beautiful limbs;” her one criticism being that they “spoiled their legs by constantly sitting under the tandour.”

Hester first would have passed through a private pavilion where groups of Turkish women reclined in semi-attire on divans, drinking coffee or sherbet. She would have stripped in a latticed cubicle, leaving her clothes and belongings to be attended by a guard. Wearing only a cotton wrap, she would have loosened her hair to enter the bathing hall. Here, she would have been led through a steam-filled enclosure, and gazed about her through archways to see numbers of women, many of rank, and their slaves, who were as naked from the waist up as their mistresses, combing their hair, massaging their limbs with rough sudsy whisks and pouring water over their bodies from copper basins. All teetered skillfully across the hot marble floors on wooden stilt-like clogs, some even carrying infants and small children, whose cries added to the cacophony. She thought their “eyes, their brows & noses are charming” and that they had “finely proportioned figures…fine busts, & beautiful limbs;” her one criticism being that they “spoiled their legs by constantly sitting under the tandour.”

Hester would probably have been directed to use a small inner room off the main chamber, everything for non-Muslims was by law separate, and she would have been regarded as an infidel. There, a female attendant, usually Anatolian, would set about the same routine that has been used for centuries; ordering her client to lie face down on the slab, then manipulating arms and legs, scrubbing, pummeling and massaging with such force it was often more painful than pleasurable. In other rooms, she might have glimpsed women wincing companionably as attendants removed hair from their arms, legs and private parts, using a warm waxen paste made of lime and arsenic water. As Hester discovered, Turkish women were fastidious about the removal of all superfluous hair: any Turkish man would have considered it a sin to find hair on his wife anywhere other than on her head. Whether Hester felt the need to experience this aspect of the hamam, neither she nor her lover at the time, Michael Bruce, ever revealed, although she rebuked him for letting his chest hair and ‘handsome brows’ be too over-enthusiastically waxed!